About.

Jaemin Bae (b. 1992, Daegu) never set out to be an artist. He knew that he wanted to work in art, but also that an artist was by no means a promising career prospect. He had heard that professional art restorers were hired by the government to work in cultural sectors, such as state-run museums. He could be a gongmuwon, a government worker, with the unglamorous but assuredly stable lifestyle that follows. This was the biggest reason he chose to study Buddhist art in college, though a lifetime of growing up in a Buddhist household certainly contributed too.

It was while undergoing this intensely specialized curriculum that his outlook shifted. Rigorous training in the use of traditional materials was paired with a strict adherence to historic techniques. It was a field where emulating the masters of millennia past, down to the most delicate hairlines, was held in utmost sanctity. Any technical deviancy was met with disapproval, and worse, bewilderment. These years left Bae with an indelible sense of discipline and a trove of knowledge on an otherwise lost art form - along with mounting frustration. Finally, he came to realize that he was not, in fact, gongmuwon material.

This renouncement allowed Bae a creative freedom, one which he relished. Holed up in his cramped studio flat in hilly Haebang-chon (“Liberation Village”), he churned out works at a remarkable rate. Liberated from the confines of tradition, academia, any lingering career doubts and even his mandatory military service (which he finished during this period), Bae was basking in that fleeting, rosy period in a young artist’s career: brimming with both confidence and zeal.

This came to an abrupt halt when his flat burned to the ground while he was slept. Waking up to heavy black smoke enveloping his bedroom, he managed to jump over the flames to safety. In the process, his body, not to mention most of his possessions and works, was ravaged.

Bae spent the next months in a hospital, heavily sedated while whole sections of his skin underwent reconsturctive surgery. For the first few weeks he could not open his eyes - his eyelids had melded shut in the intense heat. All he could discern was the vague silhouette of the sun rising and falling over the horizon, presumably through a window by his bedside. Moments of lucidity were interspersed by opioid-induced hallucinations. It was during these vivid waking dreams and pitch-dark days that the young artist faced his mortality.

Near-death experiences leading to a reavowal of faith is a common tale. For Bae, it was more of an expansion, rather than a discovery or return. He remained a painter, and a Buddhist. But reverence and prayer now made way for contemplation and reflection. This shift was not a turn to the secular, but an expanded view of spirituality: rather than being confined to the statuesque figures of buddha and bodhisattva, Bae began to paint the non-deific: the natural world, the people around him. In each of these subjects he found an inner world to capture onto canvas.

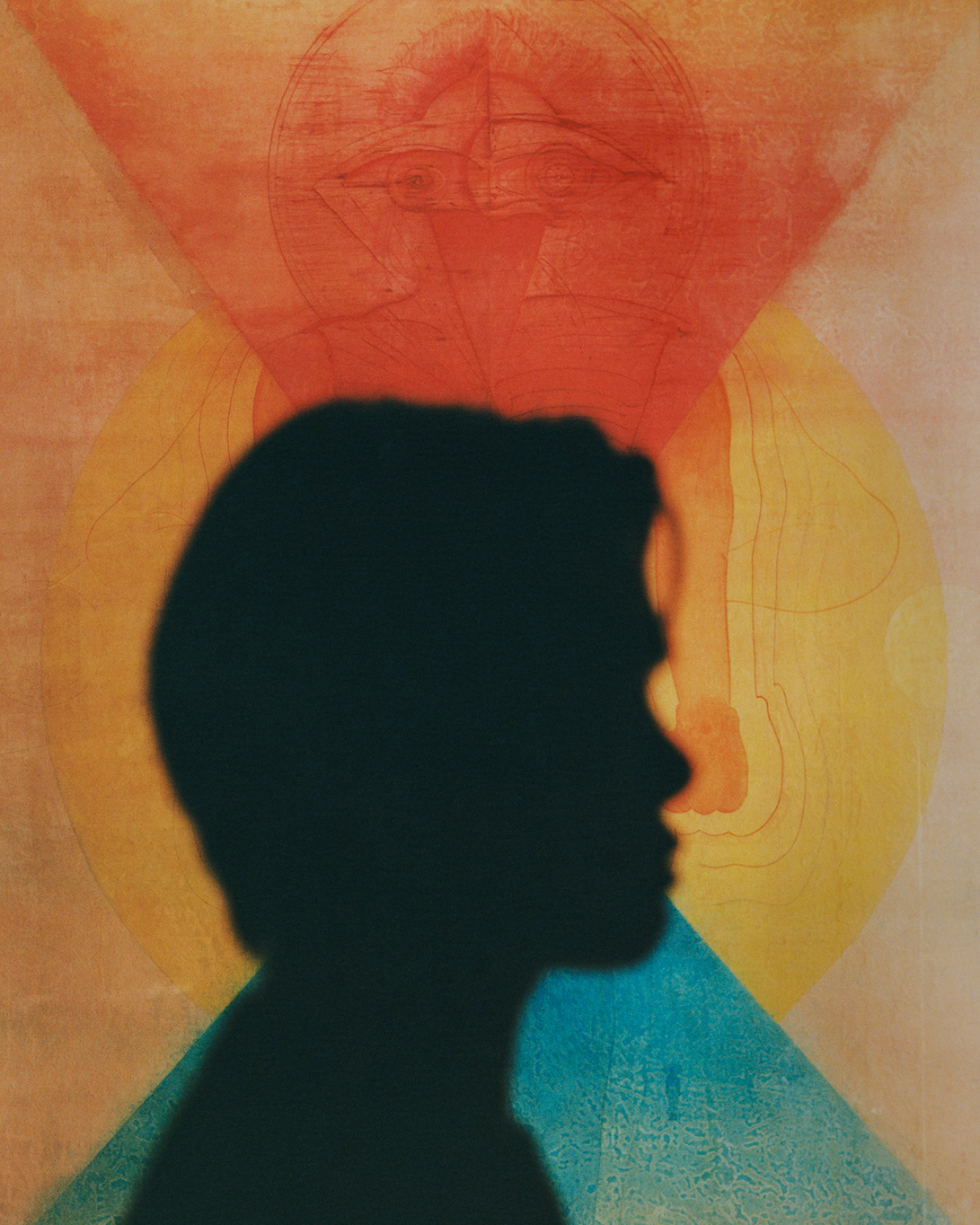

Portrait by Min Hyunwoo